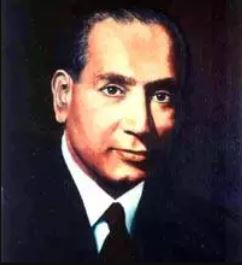

Birbal was the third child of his parents, the late Prof. Ruchi Ram Sahni and Shrimati Ishwar Devi. He was born on the 14th of November 1891, at Bhera, a small town in the Shahpur district, now a part of the West Punjab, and once a flourishing centre of trade, which had the distinction of an invasion by the iconoclast, Mahmud of Ghazni. The immediate interest that canters round Bhera is enhanced by the fact that this little town is situated not far from the Salt Range which may be described as a veritable "Museum of Geology ". Excursions to these barren ranges, where lie unmasked some of the most interesting episodes and landmarks of Indian geology, were often coordinated with visits to Bhera during our childhood, particularly to Khewra.

Here occur certain plant-bearing formations concerning the geological age of which Birbal made important contributions in later years.Bhera was his ancestral home, but his parents were at one time settled much farther a field, in fact at the reverie port of Dehra Ismail Khan on the Indus, and later migrated to Lahore. Prof. Sahni's father was obliged to leave Dehra Ismail Khan owing to reverses of fortune and the death of our grandfather who was a leading citizen of the town. With the change of fortune, life became different and difficult. Undeterred, Ruchi Ram Sahni walked with a bundle of books on his back all the way from Dehra Ismail Khan to Jhang, a distance of over 150 miles, to join school. Later at Bhera and at Lahore, he distinguished himself as a scholar. He educated himself entirely on scholarships that he won. He was thus brought up in a hard school of life, and was entirely a self-made man. Prof. Ruchi Ram Sahni was a person of liberal views, and during his career he became one of the leaders of the Brahmo Samaj movement in the Punjab, a progressive religious and social upsurge which had then freshly taken root. Undoubtedly father imbibed these ideas during his sojourn in Calcutta in his early days. He gave practical effect to his views by breaking away completely from caste. And when the call came, father, then a man of advanced years, stood knee-deep in the sacred mud of the tank of the Golden Temple and removed basket load of it upon his frail shoulders to assist in clearing the accumulated silt. His religion knew no boundaries. Always a patriot, he threw himself heart and soul into the struggle for independence and even tasted the severity of the bureaucratic baton at the Guru ka Bagh. He fought valiantly for the rights of his countrymen, and was more than once on the verge of arrest.

About 1922, when he returned the insignia of the title conferred upon him by the then government, Prof. Ruchi Ram Sahni was threatened with the termination of his pension, but his only answer was that he had thought out and foreseen all possible consequences of his action. He retained his pension ! It was inevitable that these events left their impress upon the family and were also imbibed by Birbal. If Birbal became a staunch supporter of the Congress movement, it was due in no small measure to father's living example. To this may be added the inspiration he derived, even if on rare-occasions, from the presence of political figures like Motilal Nehru, Gokhale, Srinivasa Shastri, Sarojini Naidu, Madan Mohan Malaviya and others who were guests at Ruchi Ram's Lahore house, situated near the Bradlaugh Hall which was then the hub of political activity in the Punjab. Birbal's mother was a pious lady of more conservative views, whose one aim in life was to see that the children received the best possible education. Hers was a brave sacrifice, and together they managed to send five sons to British and European universities. Nor was the education of the daughters neglected in spite of opposition from orthodox relations, and Birbal's elder sister was one of the first women to graduate from the Punjab University. Such then was the family and parental background which influenced Birbal throughout life. In later years he prided in calling himself a "chip of the old block" which he was in every sense of the term. It can be truly said that he inherited from father his intense patriotism, his love of science and outdoor life and the sterling qualities which made him stand unswervingly in the cause of the country, while he imbibed his generosity and his deep attachments from our unassuming and self-sacrificing mother.

The Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany commemorates the name of its reverend founder, Professor Birbal Sahni, one of the great sons of modern India. In September 1939 a committee of palaeobotanists working in India was formed, with Professor Sahni as Convener, to coordinate palaeobotanical researches and to publish periodical reports. The first report entitled ‘Palaeobotany in India’ appeared in 1940 and the last in 1953. On May 19, 1946 eight members of the committee, who then happened to be working at Lucknow (K.N. Kaul, R.N. Lakhanpal, B. Sahni, S.D. Saxena, R.V. Sitholey, K.R. Surange, B.S. Trivedi and S. Venkatachary), signed a Memorandum of Association to form a Palaeobotanical Society.

A trust that name was created on 3rd June, under the Societies Registration Act (XXI of 1860), with a nucleus of private funds and immovable property, a reference library and fossil collections dedicated by Professor Birbal Sahni and Mrs. Savitri Sahni, to the promotion of original research in Palaeobotany.

This trust was assigned the job for the foundation of a Research Institute. By a resolution passed on 10th September 1946, the Governing Body of the Society established an ‘Institute of Palaeobotany’ and appointed Professor Sahni as its first Director in an honorary capacity. Pending the acquisition of per manent place the work of the Institute was carried out in the Department of Botany, Lucknow University, Lucknow. In September 1948, the Institute moved to its present campus received as a generous gift of an estate comprising a large bunglow on 3.50 acres of land, from the Government of the then United Provinces. Soon plans were made for erecting a building for the Institute. The Foundation Stone for the new building was laid on April 3, 1949 by the Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

Unfortunately after a week on 10th April 1949 Prof. Sahni passed away leaving the responsibility to establish the Institute to his wife Mrs. Savitri Sahni. Untiring efforts and zeal of Mrs. Savitri Sahni led to the completion of the new building by the end of 1952. The Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru dedicated the building to science on January 2, 1953, amidst a galaxy of scientists from India and abroad. From December 1949 to January 1950, Prof. T.M. Harris of the University of Reading, England, served as Advisor to the Institute. In May 1950 Dr. R.V. Sitholey, Assistant Director was appointed as Officer-in-charge for carrying out current duties of the Director under the supervision of the President Mrs. Savitri Sahni.

In 1951, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) included the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany in its Technical Assistance Programme, under which Professor O.A. Høeg of the University of Oslo, Norway, served as its Director from October, 1951 to the beginning of August, 1953. A short time after Prof. Høeg’s departure, Dr. K.R. Surange was made the Officer-in-charge, under the supervision of the President, Governing Body of the Palaeobotanical Society. In October 1959 Mrs. Savitri Sahni, in addition to being the President of the Society, also became the President of the Institute and in charge of administration, and at the same time Dr. Surange was appointed as Director having charge of academic and research activities. In the end of 1967 a stage came when it was felt that the Palaeobotanical Society should function as a purely scientific body and the Institute as a separate organization. In January 1968, Prof. K.N. Kaul was elected as the President of the Society. A new constitution was framed in the meantime, under which Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany was registered as a separate body on July 9, 1969. Thus, the Palaeobotanical Society in November, 1969, transferred and delivered the possession of Institute to this new body whereby the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany came under the management of a new Governing Body. Since then, the Institute functions as an autonomous research organization and is funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

In spite of his academic interests, Birbal was by no means a recluse and he enjoyed in full measure the lighter side of life, though in his own way. When some of the Indian students at Cambridge staged a fancy dress celebration, he turned up as a sadhu (an ascetic), which was not altogether un symbolic of his inner self. He was extremely fond of games and retained his interest in sports for a long time. He not only represented his school and college hockey XIs but was also very keen on tennis at the Government College, Lahore. At Cambridge he represented the victorious Cambridge Indian Majlis at tennis against the Oxford Majlis.

Traverses In The Himalayas

Even as a student Birbal made one of the biggest collections of Himalayan plants at considerable sacrifice of his routine studies and examination work. He made numerous excursions to the Himalayas during which Hooker's Flora of British India was his invariable companion. He devoted a great deal of time, irrespective of other work, to the investigation of these plants, some of which, I believe, now form a part of the New Herbarium. The passion for outdoor life and trekking was acquired early. The traverses from Pathankot to Rohtang Pass; Kalka to Chini (Hindustan-Tibet road) via Kasauli, Subathu, Simla, Narkanda, Rampur Bushahr, Kilba, taking the Buran Pass (16,800 ft. high) in the stride are worth mentioning. Other traverses were carried out from Srinagar to Dras, across the Zoji la Pass; Srinagar to Amarnath (height 14,000 ft. with another climb of about 16,000 ft. en route); Simla to Rohtang (12,000 ft.) via the Bishlao Pass and thence back to Pathankot.

On his return from Europe, Birbal made long traverses independently, the most important of which was from Pathankot to Leh in Ladakh in 1920. The route followed during this traverse, carried out in the company of the late Prof. S. R. Kashyap, himself a keen botanist, was Pathankot- Khajiar-Chamba-Leh and thence back via the Zoji la Pass-Baltal-Amarnath-Pahalgam and finally Jammu. This tour lasted over several weeks and resulted in a rich collection of Himalayan plants.

Between 1923 and 1944 Birbal made a number of other traverses in the Himalayas, accompanied at times by his wife. In 1925 between Srinagar, Uri, Poonch, Chor Panjal, Pal Gagrian and thence to Gulmarg, they were marooned on the snow at Chor Panjal and arrived at Gulmarg after much hardship. In 1944 he repeated the traverse of 1923, then left unfinished owing to unavoidable circumstances. This time he was also accompanied by Prof. Jen Hsü and another colleague from the University, Dr. R. D. Misra. Their route lay between Gujrat, Bhimbar, Nowshera, Rajauri, Thanamandi, Poonch, Aliabad, Uri and finally Srinagar.

It was these treks through the Himalayas which gave him that expansive horizon, breaking through the bounds of insularity, and which enabled him to view palaeobotanical and geological problems in their widest perspective, so essential to their correct understanding. It was these accumulated experiences and his geological background, indispensable for palaeobotanists, which he brought to bear upon his views on the origins and distribution of fossil floras, and upon the geographic orientation of ancient continents and seas.

Early Quest for Science and Adventure

There was one incident which shows how early Birbal acquired his curiosity for the unknown and love of adventure. In 1905 the entire family moved to Murree for the summer. One fine morning he collected a few handkerchiefs and one or two small empty tins and asked his elder sister and brother to accompany him. Little did they realize what they were in for. They left home quietly, without a soul knowing, and descended into the ravine on the north side of the town. They descended further and further till they reached the stream. The downward journey did not seem too difficult though occasions were numerous when Birbal had to help them across ditches and boulders. In the excitement of the chase all count of time was lost, except when the pangs of hunger made things unbearable. And when they started on the return journey, it was already nearing dark.

It became more and more difficult to climb and Birbal was faced with the task of first helping one and then the other over the huge boulders which even today appear as mountains in retrospect. Night had already fallen and meanwhile the entire household was in a state of turmoil. The servants had been sent out with lanterns to look for the young explorers, little knowing where to find them, since no one imagined for a moment that they could have gone beyond the environs of the town. They reached home late at night tired, hungry and with bleeding feet, not to speak of the unrestrained stream of tears rolling down our cheeks, with the best prospect of receiving, in addition, a good talking to, to say the least. But young Birbal was quite composed, and when father asked him what he meant by leaving home without permission and taking the youngsters, too, with him, he merely answered that he wanted to collect crabs. This unusual reason almost spelt tragedy though ultimately it also proved their saving. “Crabs, indeed!" was father's first outburst and with it he took a step forward. For a moment everybody thought all was over and their backs began to itch with a queer feeling of expectancy! But such was his own love of adventure and for search after things new, that he immediately checked himself and said nothing more. Birbal accompanied his father on many excursions much more difficult and dangerous. The most notable and exciting of these was crossing of the Machoi glacier not far from the Zoji la Pass in 1911, with little more equipment than rope-made chappals for footwear and a local guide. It was here that looking down, he saw in a gaping chasm a horse standing upright, frozen and preserved in its icy grave. As he bent down to peep into the dark, awe-inspiring fissure, it gave him a shudder and a premonition of consequences, unprepared as he was for such an adventure. It was here that Birbal found and collected red snow (a rare snow alga) during the summer of 1911, just before his departure for England. A part of the sample collected was examined by Prof. Seward and is perhaps still preserved at the Botany School, Cambridge. This was a good introduction for the young botanist at Cambridge, for this alga had not been found for a long time past in India.

Besides his spirit of adventure he had in him a liberal measure of mischief in his early days. Once family stayed at Simla in the house which adjoins the Brahmo Samaj and which they shared with another family. In the small plot that lay between their residence and the Samaj building we had jointly reared vegetable garden. Somehow holiday was cut short, and family had to leave the cool heights of Simla - and of course with it the cucumbers and the half-ripened maize cobs as well. This was too much of a blow, and Birbal conceived the plan to remove all the edible fruit. As if that were not enough, the night prior to our departure, he cut off, under his leadership, the roots of the plants just below the stems with a large pair of scissors. After family left, the plants naturally began to wither slowly, steadily, mysteriously. Was it a fell disease, his erstwhile neighbors thought? They had watered the plants hard enough. Indeed the more they had been watered, the faster they had withered. But neighbors never knew of the secret till they returned to Lahore! and well remember it even now.

In later years the bent for mischief took turn for playfulness. Many will remember his favorite toy monkey which toured with him over many continents and with which he often used to amuse children. This monkey was bought in Munich from a pavement vendor. Birbal had seen some children playing with a similar monkey and was himself much amused at it. After ransacking many shops he was able to purchase an exact replica and often went to the garden where he had erstwhile seen the children at play to 'perform' during the lunch interval to the great pleasure of the little ones.

Birbal was of a rather sensitive nature. He formed deep attachments from his early days, which may be illustrated by an incident during his college career. when the results of the Intermediate examination, at which one of his close and inseparable friends had appeared, were announced. By an inexplicable stroke of misfortune his class fellow was declared unsuccessful. This created not only storm in the house, but almost spelt tragedy, because for at least two days Birbal wept like a child and refused to eat. For a number of days his movements caused anxiety, and it was only very gradually that he reconciled himself to the idea that a friend of his was left one year behind him at college.

Most outstanding was his desire for equity and fair-play. Partly by virtue of being the eldest brother at Lahore (the eldest was then in England) and partly because of his affectionate temperament, the younger brothers and sisters recognized him as an impartial arbitrator in the family. Whether it was a dispute about the ownership of a pencil or a book, or as to who should last switch off the light in the cold winter nights, we all looked to him for a decision, and what is more important, everybody abided by it.

Early Quest for Science and Adventure

Birbal's interests were wide and his discovery of the coin moulds at Rohtak in March 1936 bears witness. This archaeological discovery by a palaeobotanist, with the stroke of a geologist's hammer, symbolizes the vitality and versatility of the man. It is a tribute to his genius that not only did he make this unique discovery, but also threw himself heart and soul into the study of these coin moulds. He published his results in a masterly monograph in the journal of the Numismatic Society in 1945, setting, according to a numismatist, a new standard of research in the subject. For this purpose he set himself to the study of some of the Indian coin moulds as well as those from China. He took keen interest in all geological problems, even those that had no direct bearing upon his palaeobotanical work. But it must be said that, if one scratched him deep enough, one always found a botanist in the core.

Apart from his scientific interests, he was much inclined towards music and he could play on the sitar and the violin. He was also interested in drawing and clay-modeling and he utilized opportunities, whenever he was free from his other work, to visit the Arts School, Luc know, for further acquaintance with these arts.

Independent Outlook

There was another aspect of Birbal's attitude towards life which comes forcibly to mind and which shows his independent outlook and his love for the science to which he remained devoted throughout life, and in which he was subsequently to make a name for himself and for his country. Father was one of those disciplinarians from whom a mere suggestion was usually enough to settle where the decision lay. He and his friends had sometimes discussed what career the sons were to follow. In the summer of 1911 came Birbal's turn to proceed to England for higher studies. Birbal was asked to prepare for his departure. There could not be much argument about it, but I distinctly remember Birbal's answer: that if it was an order, he would go, but that if his own inclinations in the matter were to be considered, he would take up a research career in Botany, and nothing else. Though this astonished father for a while, yet he consented, for in spite of his strong disciplinarian attitude, he gave perfect freedom of choice in essential matters. Thus it was that Birbal took up a career as a botanist. In this case, perhaps, father's acquiescence was not so difficult, as he had been himself always keen on research and, indeed, after years of service as a professor of chemistry, he went to Manchester where he carried out investigations on radioactivity with Prof. Ernest Rutherford, results of which were subsequently published. Indeed, Birbal helped him there in photographic and other incidental work during the vacations, though he had himself to take the Natural Science Tripos, Part II, in the same year. It scarcely needs repetition that father's example gave the incentive and inspiration for research to all those around him, and not only that; he inculcated a spirit of fearless, shedding the lustre of freedom around himself which played its own part in the independence movement.

Although Birbal gained many academic distinctions but he did not plan to seek them. He invariably had an independent outlook where such matters were concerned, irrespective of consequences. Once during his B.Sc. examination of the Punjab University sitting down the Botany examination he found that question paper set was an exact, or almost exact, replica of the paper set at a previous examination. He thought that such a question paper might give undue advantage to some and an undue handicap others, and that, in any case, it could not be a fair test of knowledge. He got up, handing the (blank) answer sheets to the invigilator against all persuasion, walked out of the hall in protest. When came home within less than half an hour of the commencement of the examination and met father at the doorstep, it was a worthy sight! The surprised parent could not decide whether to show anger or laugh at situation, such as even he as a professor of long standing had never been faced with – a situation comic enough, but, nevertheless, potentially fraught with serious consequences for the University was in no way bound to set a fresh paper to please the impetuosity of a young student. The matter went to the University Syndicate. Birbal one the day, for it was decided that no examiner could be so easy going or disinterested as to pick up an earlier paper and inflict it upon the students, almost to to. A fresh paper was set for him. This shows how well he held the courage of convictions, where even an older man might have been afraid to lose a year so unnecessarily, being well able to answer the questions set.

Professor Sahni’s Contributions on Living Plants (By P. Maheshwari, Palaeobotanist 1:17-21)

In its historical aspect science may be likened to a tree which is constantly branching as the sum total of knowledge grows larger and larger and a subdivision of the field becomes necessary. Occasionally, a bud of special vigour appears and gives rise to a branch so dominating and important that it changes the contour of the whole organic body. An event of this nature seems to have happened in Indian Botany when the young Sahni graduated from Lahore in 1911 and proceeded to England to study further in the Botany School of the Cambridge University. Coming under the influence of a great master like the late Prof. A. C. Seward, he learnt rapidly, gained much insight and experience in the morphology of living as well as fossil plants and started a flourishing school of research on his return to India, which is now well known allover the world.

It is commonly believed that Prof. Sahni was a palaeobotanist, and that it was his work in this field which brought him many distinctions like the Fellowship of the Royal Society and the Presidentship of the Indian Science Congress. While this is essentially true, those like the present writer, who came in personal touch with him, would at once agree that he was a botanist of very wide interests, eager to take advantage of every opportunity in advancing our knowledge of plant life. When I was told by Dr. R. V. Sitholey, a former pupil of Prof. Sahni and my own, and Secretary to the Editorial Committee of The Palaeobotanist, that Prof. T. G. Halle would review his work on the palaeobotanical side, and that I should review that on living plants, I, therefore, readily acceded to his request and set out to prepare this brief sketch.

Sahni's first paper entitled "Foreign Pollen in the Ovules of Ginkgo and of Fossil Plants" was published in the New Phytologist of 1915, only a few years after he reached Cambridge. Here he recorded the presence of pollen grains other than those of Ginkgo in no less than eight out of about a dozen ovules of this plant obtained from Montpellier. Most of them showed the presence of two prothallial cells thus indicating their abietineous nature and one had germinated to form a tube twice as long as its own diameter.

Although an interesting observation in itself and quite indicative of the discerning power of the author, it is the latter part of the paper which specially revealed Sahni's critical insight even at that early stage of his career. He notes: “If a similar example were found in a fossil state, it would in all probability have led to a reference of the pollen grains and ovule to the same species". Further, the mere fact of germination cannot be used in support of conclusions regarding the identity of fossil pollen-grains found enclosed in ovules ".

Sahni's next paper, published in the New Phytologist of 1915, dealt with the anatomy of Nephrolepis valubilis, collected near Kuala Lumpur, Federated Malay States, by Prof. F. T. Brooks, at that time Lecturer in the Botany School of the Cambridge University. This is a very peculiar fern in which the enormously long stolons arising from the mother plant scale forest trees to a height of 16 metres. The lateral plants borne on them at intervals reach heights considerably above the mother plant which is rooted in the soil. Periodically the former are shed to the ground after which they produce their own roots. Sahni gave a detailed account of the anatomy of the stolon and the manner in which the basal protostele of the lateral plants becomes modified into a dictyostele. Unfortunately no part of the mother plant was available to him and, therefore, a fuller account could not be given.

From N ephrolepis valubilis Sahni proceeded to a study of the vascular anatomy of the tubers of N. cordifolia (New Phytologist, 1916) which are formed as terminal swellings of short branches of the underground stolons. The influence of the size factor on internal structure was very evident in this case. The strand of the branch stolon enters the base of the tuber as a solid protostele but rapidly expands in a funnel-like fashion, acquiring internal phloem, pericycle, endodermis and ground tissue. Eventually the expanded stele breaks up into a hollow network of tangentially flattened strands separated by gaps of irregular shapes and sizes. Towards the apex of the tuber the strands converge again to form a single protostele.

Soon after the publication of his papers on Nephrolepis, Sahni submitted a dissertation for the Sudbury-Hardyman Prize on the "Evolution of Branching in the Filicales" which was published in the New Phytologist of 1917. In this he showed that as a rule the branches do not hold any regular position with respect to leaves and those cases where such a relationship is found”, this association is, in its evolutionary origin, a secondary phenomenon attributable to possible biological advantages, one of which may be the protection of the young bud ". New Caledonia shares with some other islands of the Pacific the possession of a large number of endemic species which are of great interest to the morphologist and systematist. Prof. R. H. Compton of South Africa, who visited these islands in 1914, collected a number of plants among which was also the rare and little known conifer Acmopyle pancheri. Originally named by Pancher as Podocarpus pectinata, then renamed by Brongniart and Gris (1869) as Dacrydium pancheri, this plant was finally transferred by Pilger to a new genus of doubtful affinity. The generic name Acmopyle, which he gave to it, refers to the so-called apical position of the micropyle although actually it is not quite so.

The material collected by Compton was rather fragmentary and poorly preserved, but Sahni was able to produce a fairly exhaustive work on the morphology and anatomy of this plant which was submitted to the London University as a part of his D.Sc. thesis in 1919 and published one year later in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Although Coulter and Chamberlain (1917) placed Acmopyle in the Taxineae and the same procedure was followed by Chamberlain (1935) in his book on Gymnosperms, Sahni's work has made it clear that this genus is very similar to Podocarpus in the vegetative anatomy of the root, stem and leaf. Marked similarities also exist in the structure of the male cones, microsporophylls and pollen grains, the drupaceous character of the seed, and the organization of the female gametophyte and young embryo. The only important differences between the two genera are that in Acmopyle the mature seed is nearly erect, the epimatium is fused to the integument even in the region of the micropyle, and the vascular supply of the ovule is much better developed than in Podocarpus. Taking the sum total of the characters, however, it was clear that Acmopyle had to be classed in the Podocarpaceae, perhaps as one of its most highly specialized members.

In the theoretical part of the paper Sahni proposed a division of the Gymnosperms into two broad groups: (a) Phyllosperms, with seeds borne upon the leaves; and (b) Stachyosperms, with seeds borne either directly upon an axis or upon a structure which is probably some modification of an axis. The Phyllosperms included the Pteridosperms and Cycadales (also the Caytoniales), and the Stachyosperms included the Cordaitales, Ginkgoales, Coniferales, Taxales and Gnetales. The position of the Bennettitales remained doubtful owing to the uncertainty regarding the morphological nature of their ovule-bearing stalks. As remarked by Florin (Botanical Gazettel, 1948) Sahni's view that these two groups constitute a natural assemblage receives considerable support from the results of recent researches on the morphology and phylogeny of the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic conifers. An important point here is the breaking up of the stele and the formation of gaps without any influence from leaf traces which in normal fern rhizomes have been held to be the dominating factors in the evolution of a dictyostele.

Soon after the publication of his papers on Nephrolepis, Sahni submitted a dissertation for the Sudbury-Hardyman Prize on the "Evolution of Branching in the Filicales" which was published in the New Phytologist of 1917. In this he showed that as a rule the branches do not hold any regular position with respect to leaves and those cases where such a relationship is found”, this association is, in its evolutionary origin, a secondary phenomenon attributable to possible biological advantages, one of which may be the protection of the young bud ". New Caledonia shares with some other islands of the Pacific the possession of a large number of endemic species which are of great interest to the morphologist and systematist. Prof. R. H. Compton of South Africa, who visited these islands in 1914, collected a number of plants among which was also the rare and little known conifer Acmopyle pancheri. Originally named by Pancher as Podocarpus pectinata, then renamed by Brongniart and Gris (1869) as Dacrydium pancheri, this plant was finally transferred by Pilger to a new genus of doubtful affinity. The generic name Acmopyle, which he gave to it, refers to the so-called apical position of the micropyle although actually it is not quite so. The material collected by Compton was rather fragmentary and poorly preserved, but Sahni was able to produce a fairly exhaustive work on the morphology and anatomy of this plant which was submitted to the London University as a part of his D.Sc. thesis in 1919 and published one year later in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Although Coulter and Chamberlain (1917) placed Acmopyle in the Taxineae and the same procedure was followed by Chamberlain (1935) in his book on Gymnosperms, Sahni's work has made it clear that this genus is very similar to Podocarpus in the vegetative anatomy of the root, stem and leaf. Marked similarities also exist in the structure of the male cones, microsporophylls and pollen grains, the drupaceous character of the seed, and the organization of the female gametophyte and young embryo. The only important differences between the two genera are that in Acmopyle the mature seed is nearly erect, the epimatium is fused to the integument even in the region of the micropyle, and the vascular supply of the ovule is much better developed than in Podocarpus. Taking the sum total of the characters, however, it was clear that Acmopyle had to be classed in the Podocarpaceae, perhaps as one of its most highly specialized members.

In the theoretical part of the paper Sahni proposed a division of the Gymnosperms into two broad groups: (a) Phyllosperms, with seeds borne upon the leaves; and (b) Stachyosperms, with seeds borne either directly upon an axis or upon a structure which is probably some modification of an axis. The Phyllosperms included the Pteridosperms and Cycadales (also the Caytoniales), and the Stachyosperms included the Cordaitales, Ginkgoales, Coniferales, Taxales and Gnetales. The position of the Bennettitales remained doubtful owing to the uncertainty regarding the morphological nature of their ovule-bearing stalks. As remarked by Florin (Botanical Gazettel, 1948) Sahni's view that these two groups constitute a natural assemblage receives considerable support from the results of recent researches on the morphology and phylogeny of the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic conifers.

In the year 1920 Sahni published another' paper dealing with seed structure of Taxus and suggested that the Palaeozoic seeds Cycadinocarpus, Rhabdospermum, Mitrospermum and Taxospermum, all belonging to the Cordaitales, illustrated the general tendency which may have operated in producing the types of seeds found in Taxus, Torreya and, Cephalotaxus. He further proposed that these three genera were sufficiently apart from the rest of the conifers to merit their being placed in a separate order Taxales. It is interesting to observe that recently Florin (Botanical Gazette, 1948) has accepted this view, which is a fine testimony to the shrewdness and insight of Sahni even during his pre-doctorate days.

Sahni's interest in the Taxales led him to cut some sections of the seeds of Cephalotaxus pedunculata in which he discovered the presence of an apical prolongation of the female gametophyte, which surrounded by a moat-like depression into which the archegonia open, props up the nucellar membrane ( somewhat like a tent-pole. Since the tentpole is also found in several Cordaitalean: seeds, he took it to be a further evidence of the close affinity between the two groups. In 1924 Prof. Sahni, then Head of the Department of Botany at the Lucknow University, was elected President of the Indian Botanical Society which had been founded only three years earlier as the result of his own efforts and those of Profs. W. Dudgeon (Allahabad), S. R. Kashyap: (Lahore) and K. Rangachari (Madras), none of whom is with us any more. The subject of Prof. Sahni's presidential address was "The Ontogeny of Vascular Plants and the Theory of Recapitulation". Although formulated for all living organisms, the theory of recapitulation had so far derived its chief support from the zoological side. Sahni took pains to show that an equally convincing case could be made out for it on the botanical side. He cited numerous examples from ferns to support his contention, but did not fail to draw upon the gymnosperms and angiosperms and even the algae and bryophytes, and made a contribution which is fully indicative of his scholarliness and powers of reviewing facts.

The brilliant discoveries of Kidston and Lang and the great resemblances between the Psilophytales and Psilotales inspired Sahni into some studies on the latter. In 1923 he published a short paper entitled “On the Theoretical Significance of Certain So-called Abnormalities in the Sporangiophores of Psilotum and Tmespteris" based on some material of these plants collected from New Caledonia by Prof. R. H. Compton. He concluded that the sporangiophores of the Psilotales are not forked sporophylls but axial organs comparable with the branched sporangium-tipped axes of the Psilophytales. This short paper was followed by a larger and more detailed contribution published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1925) in which Sahni gave a very complete account of the morphology and anatomy of the rare species, Tmesipteris V ieiuardi. The erect and terrestrial habit and presence of medullary xylem in the stem distinguish this plant from the more common T. tannensis which grows as a pendant epiphyte and is devoid of any xylem elements in the pith. Sahni correctly compared the medullary xylem of the former with the central caulinexylem in the steles of Asteroxylon and Lycopodium and concluded that the Psilotales, especially Tmesipteris, offered a closer resemblance to the Devonian genus Asteroxylon than had been suspected up to that time. Another piece of work started by Sahni at Cambridge but completed only after his return to India (in collaboration with his pupil A. K. Mitra) deals with the anatomy of some New Zealand species of Dacrydium. As a result of this study one of these species, D. Bidwilli, had to be transferred to the genus Podocarpus. Another, D. laxifolium, was found to be peculiar in the absence of all traces of xylem parenchyma and of resin or mucilage canals in the stem, leaves or ovules. The article is concluded with a criticism of the view that Podocarpus is the most primitive member of the Podocarpaceae. The authors express the opinion that Dacrydium is the more primitive genus which gave rise on the one hand to Podocarpus (by inversion of the ovule) and on the other hand to Asteroxylon(by increasing succulence and fusion of the epimatium with the integument).

During his younger days Prof. Sahni was very fond of long treks in the hills. Once in 1908, when he was yet a college student, and again in 1920, soon after his return from Cambridge, he set out on a walking tour from Lahore to Ladakh via Chamba and the Bara Lecha.' About 8 miles from Chamba was the village of Khajiar with a beautiful meadow and lake set in the midst of a dense forest at a height of about 6,400 ft. above sea level. A curious feature of the lake is a small island thickly overgrown with tall reeds and gliding over the water like a sailing vessel before a breeze. Sahni was naturally attracted by the sight of this island and presented his observations in a paper entitled "A Note on the Floating Island and Vegetation of Khajiar, near Chamba in the N.W. Himalayas" (Journal of the Indian Botanical Society, 1927), which again speaks of his great power of taking advantage of every situation and pursuing any idea with keenness and determination. Although the facts outlined by him were inadequate for a reconstruction of the precise origin or history of the floating island, there seems to be no reason to doubt his view that there once arose around the lake an extensive reed fen of which the islet was the only persisting relic, detached like the “Plav" of the Danube described by M. Pallis in the Journal of the Linnean Society of 1916.

During his memorable voyage of the “Beagle" Captain Fitz Roy discovered a new monotypic conifer named Fitzroya patagonica, some material of which was passed on to Sahni by Prof. A. C. Seward during his Cambridge days. This he studied in co-operation with T. C. N. Singh on his return to India (Journal of the Indian Botanical Society, 1931). Besides some peculiarities in the anatomy of the leaf they described the three curious gland-like organs which are found in this plant at the apex of the female cone alternating with the last whorl of scales. Their exact morphological nature still remains problematical. The authors called attention to their superficial resemblance with naked nuclei (i.e. ovules devoid of integuments) but wisely refrained from any further commitment on their homologies. While searching for flowers on a young Ginkgo tree at Lahore in 1920, Sahni noticed some abnormal leaves shaped like the ascidia found in Ficus Krishnae and certain garden varieties of Codiaeum variegatum. The two lower margins of the triangular lamina, which in a normal leaf converge into the petiole, were bent over and fused on the upper side so as to make a funnel. While no morphological significance was attributed to this abnormality, Sahni (Journal of the Indian Botanical Society, 1933) quoted numerous instances of the occurrence of similar ascidia in several Mesozoic and Tertiary species of Ginkgo, Ginkgoites, Ginkgodium and Baiera. He ends the paper with a cryptic note: "It is indeed strange how these peculiarities sometimes tend to persist through geological time". While most university men in India look upon the summer vacation as a time of rest and pause in some hill station, this was hardly so with Sahni. He used to spend this time botanizing in Kashmir, Almora, Lansdowne and other places in the Himalayas. Away from the din and bustle of Lucknow and the pressing duties of his office, it was in these summer months that he used to do much of his thinking and planning, writing of manuscripts, and even active work at the microscope. During one of these visits to Lansdowne, Garhwal (Western Himalayas), he made some interesting observations on the fruits and seeds of Viscum japonicum Thunb. now called Korthalsella opuntia Merr. This is a very common parasite in the lower Himalayas on Quercus incana and at Lansdowne there is hardly an oak tree which is free from one or more bunches of it. The minute obovoid fruits ripen in the rainy season during the month of July and the seeds are ejected with some force to a distance of two feet or more. Microscopic examination revealed that this is due to the occurrence of a viscid layer in the fruit which swells in the presence of moisture and causes an all-round internal pressure on the seed which is relieved only by a rupture of the fruit at its apical end and a shooting out of the seed in manner comparable to the discharge of a bullet. Prof. Sahni very kindly passed on some material of this plant to me for a more detailed investigation and refers to this in his paper published in the Journal of the Indian Botanical Society of 1933. This work, I am glad to say, is now nearing completion and will be published elsewhere in due course.

In 1935 Sahni wrote a short but interesting paper entitled “The Roots of Psaronius, Intra-cortical or Extra-cortical? A Discussion" in which some very interesting observations were recorded on the anatomy of the roots of Asphodelus tenuifolius (see also MEHTA, 1934; and PANT, 19425) which is a common weed in north India during the winter season. Unlike other monocotyledons this plant has a main root which persists like that of a dicotyledon. The younger roots grow vertically downward through the cortex of this root which becomes greatly distorted. This is made possible by the activity of a peripheral cortical cambium which gives rise to several layers of periderm. The younger rootlets contribute to the girth by the formation of peripheral periderms of their own but these periderms are developed only on their outer sides, where they are in contact with the main periderm. In a full-grown plant a transverse section of the root presents a baffling appearance with as many as a hundred or more intra-cortical roots packed around the centrally placed stele of the main root. These roots are usually so densely crowded that the original cortex of the main root is practically all crushed and disorganized. At the lower end of the plant the roots are seen breaking through the sheathing periderm, either singly or in thongs of two or more, which themselves become resolved into their constituents at still lower levels. What significance these observations have in our understanding of the anatomy of Psaronius is for palaeobotanists to judge but Prof. Sahni felt that the compact root zone seen around the stele is a part of the stem itself being formed by the presence of many roots growing down through the cortex. The paper on the anatomy of the roots of Asphodelus was perhaps the last of Sahni's major contributions to plant morphology, and although his interest in living plants never faded, his own studies henceforth were devoted almost exclusively to palaeobotanical, geological and archaeological investigations. Even so he inspired many young man in India into studies on living plants. No reference to him would, therefore, be complete without a brief mention of the work of some of his pupils in this line.

While Professor of Botany at the Banaras Hindu University for a few months, Sahni encouraged N. K. Tiwary, himself a very senior botanist in India; to work on the origin of the polyembryonate condition in Eugenia. At Lucknow the first to come under his fold were S. K. Pande who has worked actively on the morphology and biology of the liverworts for upwards of twenty-five years; T. C. N. Singh, now Professor of Botany at the Annamalai University, who interested himself in the anatomy of ferns; and the late S. K. Mukherji who later went abroad and specialized in Ecology and Soil Science. K. M. Gupta, now Professor of Botany at the Dungar College, Bikaner, worked on the anatomy of some homoxylous woods and described the mode of reproduction in a moss, Physcomitrellopsis indica, collected by Sahni from Banaras; and K. N. Kaul, Professor of Botany at the Agricultural College, Kanpur, sought to classify the palms on the basis of the structure of the ground tissue of the stems. In addition, H. S. Rao, now at the Forest Research Institute, Dehra Dun, contributed an important paper on the structure and lifehistory of Azolla pinnata, which was, no doubt, inspired by Sahni's great interest at that time in the fossil history and past distribution of Hydropterideae; N. P. Chowdhury ( 1937) made a detailed study of the anatomy of some Indian species of Lycopodium; D. D. Pant ( 1942), now at the University of Allahabad, produced a detailed account of the anatomy of the roots of Asphodelus tenuifolius; and Bahadur Singh has given an interesting account of the embryology and anatomy of Dendrophthoe falcata which is in course of publication. In flesh and blood Sahni is no more with us, but the torch he lighted during the last thirty years now bums more brightly than ever and the foundation of a research institute after his name will always be a reminder of the great man who brought it into existence.

Professor Sahni’s Palaeobotanical work (By T.G. Halle, Palaeobotanist 1:23-41)

Even a cursory glance at Birbal Sahni's work on fossil plants inevitably conveys a vivid impression of its extraordinary compass and variety. His researches, in fact, ranged over practically the whole field of palaeobotany. He not only selected the concrete objects of his investigations from all major groups of vascular plants and from nearly all plant-bearing geological systems; but in dealing with this diverse material, and in his more general discussions, he approached the problems involved from every possible angle. Thus his work on fossil plants resulted in contributions to, all pertinent branches of botany, as well as to stratigraphy, palaeogeography and other related lines of geological research. One has the impression that he felt on quite familiar ground whether he was studying intricate anatomical structures, analyzing taxonomic relationships, describing fossil floras, or discussing their bearings on problems of climatic changes or supposed displacements of continents. The reasons for the comprehensive character of Sahni's work may not be evident to botanists insufficiently acquainted with the study of fossil plants and may, therefore, warrant an attempt at analysis.

It is by no means unusual in fossil botany to find that the publications of one author deal with many matters that are little related except that they concern plants of the past. The palaeobotanist is rarely free to choose his subjects solely with a view to pursuing connected inquiries into certain problems. As a rule he is dependent on the material at his disposal; indeed, most work on fossil plants has been occasioned by access to this or that collection. Fossil plants are scarce, the material is precious and its examination may not infrequently appear to be a duty. It is in fact a characteristic feature of the history of palaeobotany that even the most important advances have often been made by studying and describing accidentally discovered or acquired material. Kidston and Lang, for instance, did not set out to inquire into problems of general morphology. Their primary task was to examine, analyses and describe the structures of the petrified plant- remains from the Devonian of Rhynie; but their work, nevertheless, profoundly influenced our conception of certain fundamental problems connected with the morphology of vascular plants. No doubt the claims of the material often had a particular significance in Sahni's case. His country is rich in fossil plants, and important un described collections as well as imperfectly explored plant-bearing deposits awaited his attention when, at first quite alone, he began work in this vast field. No doubt he was often inspired by a sense of duty not only to botanical science but also to the needs of Indian geology.

At the same time Sahni's researches largely group themselves along certain lines of connected study, which he evidently chose in preference to others because of their bearings on questions of general importance. A very considerable part of his work was also concerned with the analysis and survey of problems which could be studied without direct reference to concrete material. On the whole it would appear that the diversity of his researches was largely an expression of the wide range of his interests, his extensive knowledge and intellectual versatility. Some of the characteristic features of his many- sided scientific personality became apparent at a remarkably early stage of his career as a research worker.

There can scarcely be any doubt that Sahni was first attracted to palaeobotany through the influence of the late Professor Sir A. C. Seward, his teacher at Cambridge. After graduating in 1914, he began research at the Botany School where, under Seward's leadership, studies of living and extinct plants were combined to an extent at that time unparalleled elsewhere. At first Sahni engaged in morphological and anatomical investigations of recent plants, chiefly pteridophytes and conifers. Before long he also took up palaeobotanical work, while continuing his studies of living plants. For the remainder of his stay at Cambridge, till he returned to India in 1919, he divided his time between these branches of research, doing a surprising amount of excellent work in both.

Morphology of Recent Plants

Sahni's work on living plants will be reviewed separately by Dr. P. Maheshwari. But certain palaeobotanical aspects of his early studies cannot be altogether passed over here. One of the questions dealt with in the theoretical part of his publication on Acmopyle (1920a) was concerned with a palaeobotanical matter: the relation of the Cordaitales to the pteridosperms and the conifers. Sahni did not at that time definitely reject the prevailing idea that the Cordaitales were derived from the pteridosperm stock; but he advanced strong arguments against this view and his criticism was later shown to be justified by Florin's comprehensive studies. Sahni's views on various questions relating to the conifers, too, were more in accord with our present knowledge of the oldest fossil conifers than were those of most contemporary authors. In discussing the important problem of the position of the seed in the gymnosperms, he introduced a conception of great general interest from a rialaeobotanical point of view. On the basis of one single but important morphological feature he suggested a division of the gymnosperms into two groups: “Phyllosperms", with leaf-borne seeds, and “Stachyosperms" in which the seed is seated directly on a normal or modified axis. This distinction - accepted in a morphological sense rather than for practical use in taxonomic classification -is reflected in the views of later workers in phyletic morphology (e.g. Zimmermann, Florin). It has even been extended to apply to the position of all sporangia in vascular plants (" Phyllospory" and “Stachyospory" of H. J. Lam).

Sahni's views on the phylogeny of the stachyosperms were decidedly advanced. He pointed out the strong evidence against a derivation of these plants from megaphyllous ancestors, and was inclined to regard the position of their megasporangia on caulinar branches as a primitive feature. D. H. Scott expressed similar thoughts at about the same time; but it was not until ten years later that W. Zimmermann introduced the telome concept in his Phylogenie der Pflanzen, and more than another ten years were to pass before direct evidence was brought forward by Florin in the case of the conifers and the Cordaitales. It would be interesting to know whether Sahni - like Zimmermann at a later date was influenced by Kidston and Lang's discovery of the axial and terminal position of the sporangia of the Psilophytales. He did not quote the first Rhynie paper, which had appeared about two years earlier, but this may be due to a natural reluctance to enter into comparisons with plants so remote in systematic position and geological age. Only three years later he showed that he was fully alive to the consequences of the Scottish discoveries by his study of the sporangiophores of the Psilotaceae (1923, 1923 b ).

n his early work on living plants Sahni followed the

example of his

teacher by

mostly choosing those groups which particularly invite comparison with

the fossils. It

was almost

inevitable that from the first he came to adopt a phyletic view in his

morphological

interpretations

and thus to stand out as a decided adherent of what has been named "the

new morphology"

(H. HAMSHAW

THOMAS, 1931). His discussions of phylogenetic relationships at this

time throw a vivid

light on his

analytical mind and his interest in general problems. But they also show

that at an

early date he had

acquired a remarkably extensive knowledge of the morphology and anatomy

of both living

and fossil

pteriodophytes and gymnosperms. One cannot but be impressed with the

large amount of

high class work

which he crammed into the years he spent at Cambridge, dividing his

time, as he did,

between various

little related and most difficult subjects.

Sahni's first contributions to pure palaebotany, too, were products of

his research work

at the Botany

School. With an interval of only a couple of years between them he

published papers on

two widely

different groups of palaeobotanical subjects:

- The anatomy and morphology of Palaeozoic ferns, and

- The fossil Plants of the Indian Gondwana formations.

His later publications, too, are largely concerned with these two fields of investigation. It was fortunate for palaeobotany, no less than for Sahni himself, that, at the very outset of his scientific career, his attentIon was thus attracted to fruitful branches of research which were to hold his interest to the end of his life. We have Sahni's own words to prove that this important first choice of subjects was chiefly inspired by Seward. Even after Sahni had left England, Seward continued to take a great interest in his gifted Indian pupil who, in after years, frequently expressed his gratitude to the founder and leader of the Cambridge school of palaeobotanical research.

Birbal Sahni’s Contribution to Indian Geology (By S.R. Narayana Rao, Palaeobotanist 1: 46-48)

For more than three decades, since the completion of Feistmantel's classic work on the Indian Gondwana flora in 1886, the study of fossil plants had suffered a serious set-back as Indian geologists were sceptical regarding their value in geological chronology. Geologists were largely influenced by the attitude which W. T. Blanford took up in 1876 that the evidence founded upon fossil plants should be received with caution, and that such evidence was in some cases opposed to the evidence furnished by marine faunas. The year 1920, in which Seward and Sahni's volume on the revision of Indian Gondwana plants appeared, is a landmark in the history of Indian geology and palaeobotany: this year marks the revival of palaeobotanical research in India with plant fossils coming more and more into the picture of Indian geology. Prof. Sahni was a rare combination of the botanist and the geologist and the unique position he held in both the sciences made him eminently suited to bridge the gulf that separated them. He did more than anyone else to convince the geologist that study of plant fossils yielded results of a far-reaching nature which the geologist could not afford to ignore.

To Prof. Sahni plant fossils were not just chance relics of ancient floras; they had a deeper significance to him. Their geological background and implications were always present in his mind. His work, at every stage, impinged upon the domain of geology, and the field of palaeobotany became a meeting ground for botanists and geologists in this country. In a memorable address delivered to geologists in 1926, he expressed that fossil plants represent the debt that botany owes to geology. In return, palaeobotanical research which he initiated has not only been helpful in solving stratigraphical problems, but has also thrown light upon questions of palaeogeography, past climates and even earth movements. At the same time it has made its contributions to economic geology.

It is difficult to give an adequate idea, within the space of a brief article, of the extent to which he influenced geological thought and research in India within the last two decades and more. It was in this country that the first Glossopteris was discovered and the great problems in geology concerning the Gondwanaland were raised and discussed. The Gondwana problems naturally attracted a good deal of his attention. Two other chapters of Indian geology where his researches had their repercussions were the Deccan Traps and the Punjab Saline Series. He realized the importance of micropalaeontology, both in its academic and applied aspects, and the micropalaeontological technique which he had already employed in his work on the Saline Series was extended to other problems: in elucidating the Tertiary sequence of Assam and as an aid to the measurement of geological time in India.

Feistmantel's original classification into Upper, Middle (with Parsora stage as a transitional stage) and Lower has been questioned by later geologists, particularly Cotter and Fox. Fox thought there was no justification for Middle Gondwanas as there was a floral break above the Panchet stage. He further included the Parsora stage in the Jurassic. Prof. Sahni, however, did not agree that the Parsora flora was Jurassic and, on the other hand, he thought it was not younger than the Trias and possibly as old as the Permian. The geologists, again, considered the upper age limit of the Gondwanas as Lower Cretaceous, as Lower Cretaceous ammonites are found associated with the east-coast Gondwanas. In this connection the silicified flora of the Rajmahals received a good deal of attention from Prof. Sahni. Feistmantel's account of this flora was mostly confined to leaf impressions and in recent years many fossil-bearing localities had been discovered. From a critical examination of the petrifactions, Prof. Sahni came to the conclusion that the flora was Jurassic with not a single species characteristic of the Cretaceous.

A problem in which he took a great interest for many years was that of continental drift. Whereas Wegener thought that continents had broken up by drifting apart, Prof. Sahni, on palaeobotanical evidence, elaborated a complementary theory that continents once separated by oceans had drifted towards each other. In 1934 his first contribution on the silicified flora of the Deccan Intertrappean beds appeared, and with this was revived a geological controversy which dates back to the time of the pioneer geologists Hislop and Hunter. As against the Cretaceous age put forward on geological grounds by Blanford and others, Prof. Sahni found that the flora was distinctly Eocene, and it is gratifying to note that the Eocene view later received its strongest support from the geologists themselves.

For more than sixty years, the age of the Saline Series had been a baffling problem to Indian geologists and the way in which Prof. Sahni was attracted to this problem may be stated in his own words (1947): “About four years ago, while with a party of students in the Salt Mine at Khewra, it occurred to the author to dissolve a little of the saline earth and to examine some drops of the brine under the microscope. The idea was that since the salt must have been formed from sea-water by the drying up of a bay or lagoon, the brine ought to show at least some minute traces of organic remains which might give a clue to its geological age. The surmise proved to be correct: quite a number of little shreds of woody tissue of dicotyledons and conifers, as well as the chitinous remains of winged insects, were discovered. These fragments had no doubt been washed into the water or wafted on to its surface by the wind; and it was clear that if these creatures were alive at the time the sea existed, the salt could not possibly be so old: as the Cambrian”. This view necessitated the introduction of an overthrust between, the Saline Series and the overlying Cambrian beds. Dr. Gee and other field geologists, however, maintain that the Saline Series of (the Salt Range is in its normal stratigraphical sequence and, therefore, Pre-Cambrian in age. The critical evidence proving the Saline Series to be the lowest exposed member of the Salt Range Cambrian is the nature of the junction of the series and the overlying Cambrian beds. This junction, according to Dr. Gee, is an undisturbed sedimentary one and the problem, therefore, is to discover how Prof. Sahni's microfossils were introduced into the Cambrian sequence. To Dr. Gee's arguments, Prof. Sahni replied (1947): "Enough has been said to show that the field criteria upon which reliance is placed by the geologists of the Cambrian school are not safe criteria. The Salt Range question which has so long baffled us is no longer a problem of local significance: we must learn to judge it by standards based upon wider experience... Between the testimony of the rocks and the testimony of the fossils there can be no real conflict. When the two do not seem to agree, it is the direct evidence of the fossils that is to be relied upon: palaeontology is a surer foundation for stratigraphy than field evidence."One aspect of geology in which he was particularly interested in later years was micropalaeontology regarding which he states: "The last few decades have seen the rise of micropalaeontology to a position of considerable importance in geology, particularly in the quest for oil. Although it was the academic geologists who first realized the scientific value of microfossils, we owe the main developments in this field to the applied geologists, and particularly to the palaeontologists employed in the oil and coal industries."Regarding further applications of this branch of study, he writes: "We now know that not all sedimentary formations which outwardly appeared to be unfossiliferous are really devoid of organic remains. Some of these have recently been shown to be astonishingly rich in micro- fossils representing both plant and animal groups. The Saline Series in the Salt Range of the Punjab is a good case in point, so also the glacial tillites at the base of the Gondwana system in Australia and South Africa - and quite recently organic remains have also been detected in the Talchir Boulder Bed near Chittidil in the Salt Range. Owing to their wide dissemination in the body of the rock-matrix microfossils can sometimes provide an age index even if small bits of the rock collected at random are analyzed. ...There are great areas in India, particularly in the Peninsula, covered by ancient sedimentary rocks of unknown or disputed age. Very few megafossils have been found in these strata, nor are we likely to find many more in the future. An attempt may usefully be made to recover microfossils from samples of these rocks which should be collected from localities and horizons by geologists who best know the areas." His activities were, however, not confined to the laboratory; he believed that palaeobotanists should have experience of field-work and missed no opportunity of visiting fossil localities with his hammer, note-book and Leica. The Salt Range, the Rajmahal Hills and the Deccan Intertrappean areas were all familiar grounds to him. His field-notes of the Salt Range (preserved among his unpublished manuscripts) bear testimony to his keen and shrewd perception and understanding of complicated geological structures. Those who accompanied him in his geological excursions retain vivid memories of a personality full of physical and mental vigour, never sparing himself and with an unbounded enthusiasm for fossil collections and field data. A few weeks before his death he led "an excursion to the Rajmahal Hills. Those who were with him can never forget the thrill and joy with which he greeted the discovery of the Williamsonia-bearing beds near Amarjola. Among several projects he had planned for the Institute of Palaeobotany, mapping of the plant-beds of India held a high priority. He was also anxious to lead an expedition to the Spiti region of the Himalayas.

He took very great interest in geological research and teaching in Indian universities and it was due to his efforts that the subject was introduced in many of the universities. He was the Head of the Geology Department of the Lucknow University since its inception in 1943 : his inspiring lectures on dynamical geology and palaeobotany and the singular success he achieved in stimulating and training young talent for research soon made the Department an important teaching and research center for geology in this country.

He had close friendships and strong scientific connections with leading geologists allover the world, and no geologist from any part of the world while visiting India ever missed the opportunity of meeting Prof. Sahni in his laboratory and museum at Lucknow. The voluminous scientific correspondence he has left behind forms a very valuable record of contemporary geological thought and trends. No notice of Prof. Sahni's work or life would be complete without a reference to his wife, Srimati Savitri Sahni, whose understanding sympathy and companionship meant everything to him. She always accompanied him on his scientific travels and took part in many of his geological excursions. Her unflinching devotion in no small measure contributed to the great scientific achievements of Prof. Sahni.

- Degree of D. Sc., Cambridge University, 1929.

- Vice-President, Palaeobotany section, 1930 and 1935.

- Fellow of the Royal Society, London, 1936.

- General President, Indian Science Congress, 1940.

- President, National Academy of Sciences, India, 1937-1939 and 1943-1944.

- President, International Botanical Congress, Stockholm, 1950.